Complex adaptive system mechanisms, adaptive management practices, and firm product innovativeness

- 1. bs_bs_banner Complex adaptive system mechanisms, adaptive management practices, and firm product innovativeness Ali E. Akgün1, Halit Keskin2, John C. Byrne3 and Özgün Ö. Ilhan4 1 Science and Technology Studies, Gebze Institute of Technology, Gebze- Kocaeli, Turkey. aakgun@gyte.edu.tr; alieakgun@gmail.com 2 Science and Technology Studies, Gebze Institute of Technology, Gebze- Kocaeli, Turkey. keskin@gyte.edu.tr 3 Lubin School of Management, Pace University, New York, New York, USA. jcbyrne@optonline.net 4 Science and Technology Studies, Gebze Institute of Technology, Gebze- Kocaeli, Turkey. oozturk@gyte.edu.tr As a fascinating concept, the mechanisms of complex adaptive system (CAS) attracted many researchers from a variety of disciplines. Nevertheless, how the mechanism-related variables, such as strategic resonance, accreting nodes, pattern forming, and catalytic behavior of organization, impact the firm product innovativeness is rarely addressed empirically in the new product development (NPD) literature. Also, there exist limited studies on the antecedents of the mechanisms of CAS in the NPD literature. In this respect, we identified and operationalized the adaptive management practices, which involve bonding, nonlinear, and attractor behaviors of management, as antecedents of mechanisms and firm product innovativeness. By studying 235 firms, we found that (1) strategic resonance and accreting nodes are positively related to firm product innovativeness, (2) bonding, nonlinear, and attractor behaviors of management positively influence the mechanism variables, and (3) market and technology turbulence impact the adaptive management practices. We also found that mechanisms of CAS partially mediate the relationship between adaptive management practices and firm product innovativeness. 1. Introduction C hanging trends in technology and customer needs in turbulent and unpredictable environments require firms to become more aware of their adaptability for sustainable competitive advantage in general, and the development of successful new products, product innovativeness, in particular 18 (Hansen and Serin, 1993). In this sense, scholars emphasize the importance of complex adaptive systems (CAS) view, which in general indicates a system that emerges over time into a coherent form, and adapts and organizes itself without any singular entity deliberately managing or controlling it (Holland, 1995; Buckley, 2008), to gain insights for successful product development efforts under the © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

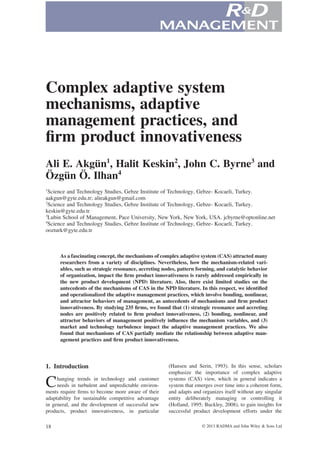

- 2. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness turbulent environmental conditions in the new product development (NPD) literature (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1998; McCarthy et al., 2006). For instance, McCarthy et al. (2006, p. 439) wrote that ‘[a] CAS framework views individual NPD processes as adaptable or malleable systems capable of producing a range of behaviors to suit different innovation expectations, levels of market uncertainty, and rates of change’. Nevertheless, studies on the CAS in the NPD context are limited, and most of them are theoretical arguments on how the CAS view is generally applied to product development process or stages (e.g., Cunha and Comes, 2003; Chiva-Gomez, 2004; McCarthy et al., 2006). While these studies show how a CAS works in product development efforts in projects or organizations, we need a greater understanding of the enabling conditions and the mechanisms of CAS in particular to adequately examine or exploit the viewpoints of its theory. The mechanisms of CAS in general indicate the dynamic behaviors that produce complex outcomes, such as innovation, as found in the management literature (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). The mechanisms of CAS enable people, groups, or departments in the organization to move beyond thinking about individualistic efforts (Harkema, 2003; Buffington and McCubbrey, 2011), and offer them a way to generate an understanding of the dynamic practices and processes to implement adaptiveness during product development activities (Garud et al., 2011). However, given the importance of mechanisms of CAS, interestingly, little attention was given to the operationalization and the empirical implications or validation of these mechanismrelated variables on the success of new products in the NPD context. In this respect, Pathak et al. (2007, p. 564) also wrote: A model of CAS behavior should precisely state how to measure the relevant constructs, how the constructs are related, and how certain mechanisms affect those constructs. Only when these issues are clearly stated can the theory be validated and examined for consistency with the phenomena under study across a wide range of situations. Also, from a managerial point of view, a study on the antecedents or drivers of the mechanisms is missing – which warrants an empirical analysis, in addition to the consequence of mechanisms on firm product innovativeness. To solve the above issues, we primarily adapt the CAS model of Uhl-Bien et al. (2007), which provides a theoretical framework for mechanism of CAS. It should also be noted that while the CAS © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd model of these authors is argued in the leadership context (i.e., at the individual level), it is highly abstract, implicit, and not operationalized. We leverage their views to an organizational level and in the product innovation context. Here, mechanisms of CAS are the dynamic behaviors, processes, and practices that occur within the product development efforts to leverage the firm innovativeness. The mechanisms of CAS include resonance (i.e., agents acting in concert), accreting nodes (i.e., the collection of many small ideas and inputs that rapidly expand in importance), pattern formation (i.e., adaptive and dynamic interpretations of events and situations), and catalytic behaviors (i.e., behaviors that speed up or enable certain activities) (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). For antecedents of the CAS mechanisms, based on the complexity leadership (CL) theory of Uhl-Bien and Marion (2009), we use the ‘adaptive management’ practices. The rational is that an adaptive management perspective does not restrict management with hierarchical positions or roles; instead, it views management as a key element of the organizing process in adaptive efforts throughout the organization, such that adaptive management can be viewed as a social influence practice and behavior of management through which emergent coordination (i.e., evolving social order) and change (e.g., new values, attitudes, approaches, behaviors, and ideologies) are constructed and produced to cope with turbulent conditions in the CL perspective (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1998; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). Based on the theoretical study of Uhl-Bien and Marion (2009), we operationalize adaptive management as practices involving bonding behavior (i.e., creating dynamic linkages and interactions), nonlinear behavior (e.g., derived by an asymmetrical, dynamic, and chaotic attitude), and attractor behavior (i.e., acting as tags and creating attractors) of management. Therefore, the aim of this study is to operationalize and empirically test the impact of mechanisms of CAS and adaptive management practices on firm product innovativeness to further enhance the literature on organizational innovation and complexity science. Also, this study attempts to improve the precision of CAS and CL theories through expanding and refining their existing theoretical conceptualizations in the innovation context. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1, this study investigates (1) the role of mechanism variables on firm product innovativeness, (2) the impact of the adaptive management practices on the mechanism variables, (3) the mediator role of mechanisms of CAS between adaptive management practices and firm product innovativeness, and (4) the R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 19

- 3. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan H9 Adaptive management practices • Bonding behavior • Nonlinear behavior • Attractor behavior Env. turbulence • Market • Technology H8 (mediator) Firm product innovativeness H5-H7 H10 • • • • Mechanisms of CAS Strategic resonance Accreting nodes Pattern formation Catalytic behavior H1-H4 Control variables • Size • Age • Industry Figure 1. Proposed model. CAS, complex adaptive system. triggering/enhancer role of environmental turbulence (including market and technology turbulence) on the adaptive management practices and mechanism variables. 2. Mechanisms of CAS and adaptive management practices The mechanisms of CAS show the necessary conditions under which complex and dynamic behavior will occur in organizations, and include resonance, accreting nodes, pattern formation, and catalytic behavior (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). Resonance, following CAS researchers, for example, Uhl-Bien et al. (2007, p. 308), is defined as ‘acting in concert . . . more specifically to situations in which the behaviors of two or more agents are interdependent’. In the innovation management literature, a similar definition of resonance can be found in the study of Brown and Fai (2006), addressing the automobile and computing industries, and is labeled as ‘strategic resonance’. Here, we believe that the well-established concept of ‘strategic resonance’ can be applied to the product innovation efforts in the organization and can illuminate the abstract definition of resonance in the CAS literature. Brown and Fai (2006), for instance, mention that strategic resonance is a dynamic, organic, ongoing, and strategic process that is about ensuring continuous linkages and harmonization between the market and the firm’s operation capabilities, firm’s strategy and its operations capabilities, and within all functions and all levels within the firm. Another mechanism variable is the accreting nodes. Accreting nodes indicate the notion of ideas that rapidly expand in importance and which accrete 20 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 related ideas (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007, p. 308). Pavlovich (2009) expands that notion of accreting nodes based on the unfoldment/enfoldment principle of information or knowledge, and mentions that accreting nodes indicate the self-organization and reciprocal creation of ideas, information, and knowledge. Here, the idea is that information/knowledge is developed and self-regulated through a procedural memory and transactive memory system (Boal and Schultz, 2007). No matter how much information/ knowledge is developed, core information/knowledge is inherent in each, despite an ongoing flow and change of components (Pavlovich, 2009). Within this process, new information/knowledge evolve through complex, flexible, and nonlinear modes of self-organization in an organizational and learning context as can be seen in the fuzzy front end or concept development stages of the product development process (Reid and de Brentani, 2004). Scholars (e.g., Cacioppe and Edwards, 2005; Boal and Schultz, 2007; Pavlovich, 2009) note that accreting nodes are manifested in organizations through how an idea or information/knowledge (1) is magnified iteratively or successively, as in a recurring growth pattern, (2) proceeds through self-consistency and fancy complementary beliefs, and (3) reweaves through the web of organizational metaphors, stories, symbols, and rhymes. Pattern formation is another mechanism of CAS. It illustrates the process of crystallizing ideas, and making sense of events, information, and complex situations in the organization and its environment, to enhance the explanatory and/or design capability of people (Kurtz and Snowden, 2003). It is obvious that this definition of pattern formation is broad and overlaps with the definition of ‘organizational © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 4. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness sensemaking’ (Weick, 1995). In this regard, we adapted the concept of ‘patterning of attention’ from Hunt et al. (2009) and Osborn et al. (2002) to clarify and better operationalize the concept of pattern formation for the CAS view of product innovation. The patterning of attention, as a sensemaking mechanism, indicates the collective process whereby people identify what is important and relevant in moving toward desired ends (Osborn et al., 2002). Especially, Hunt et al. (2009, p. 514) wrote that: From a traditional viewpoint, patterning of attention . . . stimulates social construction to create new information and knowledge from the dialog and discussion of all participants. From a complexity perspective, these influence attempts may alter N, K, P and C. That is, new individuals within the system may be included (a change of N), new combinations of interaction may be fostered (a change in K), new schema may emerge (a change in P), and new connections with those traditionally outside the system may be made (a change in C). Based on this view, we believe that it is the process of selecting what is important for product development process, and how this is to be achieved in the organization is a critical aspect of firm strategy and product development efforts in the CAS perspective. Pattern formation or patterning of attention can be seen in the organization when people (1) build a coherent structure or a description of a successful solution to product-related problems; (2) emphasize selfadjustment and development of the firm strategy to address the concurrent environmental turbulence, and expand the notion of influence patterns, such as patterning which revolve around the issues of efficiency, quality, innovation, and profitability, etc.; and (3) seek understanding of the situation via dialogue, storytelling, and discussions, and use different viewpoints to make their ideas/information prolific and vibrant (Hunt et al., 2009). The last mechanism variable is the catalytic behavior. Catalytic behavior shows the ability of accelerating and enabling activities by the addition of catalysts in the organization (Marion and Uhl-Bien, 2001; Morse, 2010). Catalysts are parts of the social interaction system that enable adaptive actions, such as seeing the bigger picture, understanding interrelationships, and bridging the communication gap among people or functional units (Holland, 1995; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). From the CAS perspective, catalysts are also considered as internal and external new information or knowledge that prompt firms to recognize new options, reevaluate existing options, © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd or revisit previously discarded options (Morris, 2005). Further, catalysts in an organization are people, ideas, dreams, new technologies, symbols, group myths, or beliefs, which provide filtering as well as cooperation and speeding up of events and actions (Morse, 2010). In addition to the mechanisms of CAS, we also discuss the term of adaptive management. Adaptive management from the CL perspective is a social influence practice that occurs within an organization in order to provide sufficient structure and enable managerial behavior in favor of firm adaptability and innovation (Marion and Uhl-Bien, 2001; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007; Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). Based on the CL theory, adaptive management involves practices of bonding, nonlinear, and attractor behaviors of management (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). Bonding behavior, a function of the network dynamics of CAS theory, is the ‘linking up’ practice through which social networks and network structures form and evolve (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). As Barczak et al. (1987) mention, bonding behavior forms knowledge worker communities, cultivates greater sense of community, trust, respect, and shared vision, and leverages knowledge transfer and generation. From an operationalization perspective, a bonding behavior of management is manifested by to what extent management (1) fosters the development of moderately coupled structures in which ideas can emerge freely and match, (2) encourages information flows by building personal networks of interconnectivity and linkages, (3) injects ideas and information into the system for its members to ponder and process, and (4) embraces diversity indicating its level of comfort with divergent or conflicting ideas (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). Nonlinear behavior is another adaptive management practice. In the CL context, nonlinearity indicates the asymmetrical relationships embodied in the organization, feedback loops among the people, as well as recurrency, which means that any activity of people can feed back onto itself (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). We believe that nonlinear behavior demonstrates the dynamic and sometimes chaotic attitude of the management in the organization. This is such that management maintains the organization at the edge of chaos, seeks to spawn emergent behavior and creative surprises rather than to specify and control organizational activities, and creates organized disorder in which dynamic events happen at multiple locales within the organization (Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). Nonlinear behavior of management also incorporates the idea that time and history matter, such that the past is co-responsible for the present behavior as well as the future (Osborn et al., R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 21

- 5. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan 2002; Boal and Schultz, 2007; Mischen and Jackson, 2008). In this way, management connects the past, present, and projects the future through storytelling (Boal and Schultz, 2007; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007). The last adaptive management practice is attractor behavior. Attractor behavior of management from the CL perspective is related to the use of attractors to enhance adaptiveness in the organization. It should be noted here that attractors come in different ‘flavors’ in the complexity theory, such as point, periodical, and strange attractors (Kauffman, 1993; Merali, 2006). Consistent with the scholars in the CAS literature (e.g., Osborn et al., 2002; Boal and Schultz, 2007), we focus on the strange attractors in this study. Strange attractors describe a system that functions in complex but inherently unpredictable ways, but that concurrently self-organizes into emergent order and structure (Pryor and Bright, 2007). In this way, the possibilities of evolution, adaptability, and change are associated with strange attractors (Boal and Schultz, 2007). In the management literature, strange attractors define the boundaries within which system behavior can occur and are analogous to the culture and climate of an organization (Cox et al., 2009). In a sense, a strange attractor is defined as a trajectory of behaviors (although the exact path is unknown) that draws people into it and influences their behaviors in the organization (Osborn et al., 2002; Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). For example, values, fads, identity, vision and mission, social assumptions, relationships, and structures function as attractors in an organization (Barczak et al., 1987; Pryor and Bright, 2007). Here, using attractor behavior, management becomes aware of the potential of such dynamic behavior, and works to repeat and/or enhance attractors’ potentials. Recognition of the effects of such attractors may be seen and act as tags (e.g., a flag or symbol around which everyone rallies) (Boal and Schultz, 2007; Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009). 3. Hypothesis development 3.1. Mechanisms of CAS and firm product innovativeness We argue that strategic resonance leverages product development efforts by amplifying the meaning of the information, and leads to an increase in its content and receptivity. For example, Mann (2002, p. 88) notes that ‘resonance is a potent force lever capable of amplifying small inputs into large outputs’. In particular, people can develop new concepts and information through exposure to diverse 22 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 and opposing views, ideas, and capabilities, and validate the re-creation of new information, knowledge, and capabilities with strategic resonance (Bennet and Bennet, 2008). Strategic resonance also provides ‘mutuality’ in the organization to improve product development efforts. As the people or departments performing different functions interact, they both give and receive resources (e.g., ideas, information, capability, etc.) during the product development process; continuous linkages and harmonization among their actions, capabilities, resources, etc. are created so that they are able to adapt to the challenges they face individually together in a mutually beneficial manner. In a sense, people or departments work together, albeit with their potentially conflicting views, capabilities, and competition for the same resources (Brown and Fai, 2006), synchronize their emotions and enhance their collective energy (Humphrey et al., 2008), and develop an appreciation of each other’s knowledge/capability limitations and responsibilities (Taylor et al., 2002) through strategic resonance. Strategic resonance further helps people or departments take different functional approaches simultaneously – leveraging product development efforts (Brown and Fai, 2006). For instance, resonance among departments or functional units provides a dynamic view of technology and marketrelated information, and helps them see taken-forgranted events in a new light, based on the perceived similarities with their domains (Turner, 2007). In addition to viewing events in a new light, people recognize that information/knowledge regarding the technical or marketing aspect of the tasks may be located anywhere in the organization (Burns and Stalker, 1994). Therefore, we hypothesize that: H1: Strategic resonance is positively related to firm product innovativeness. Accreting nodes (e.g., expanding information or knowledge iteratively) impact product innovativeness by effectively gathering information or knowledge in the organization. For instance, through accreting nodes, project-related new information or knowledge develops within the interrelations among people/functions, and it is then structured in a manner that allows people to achieve multiple courses of action during the product development process (Hawes, 1999). This is such that people develop new perceptions, views (i.e., mental models), and knowledge bases to respond unpredicted changes about projects, its environment, and organization in a flexible manner (Tharumarajah et al., 1996). Accreting nodes also enhance the crossfunctional integration and collaboration, improving product innovation efforts. For example, when © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 6. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness product-related new information is disseminated verbally throughout the organization, new engagements among people may be realized. This is because people create recursive relations and interactions for product-related information expansion and dissemination (Hawes, 1999). Also, social interactions among people reproduce, mediate, and transform information, and create cohesion where people are simultaneously autonomous and cooperative for information expansion (Pavlovich, 2009). This way, people better understand the whole product development process and discover product-related problems more effectively in order to improve its success in the marketplace. Therefore: H2: Accreting nodes are positively related to firm product innovativeness. We put forward that pattern formation (i.e., patterning of attention) enhances product development efforts by improving the problem-solving abilities of people. For example, pattern forming makes productrelated problems and issues more visible to more readily allow people to take the needed actions, and aids people against ill-prepared product-related problems (Kurtz and Snowden, 2003). Pattern formation also helps people see the product development process in a holistic way, thereby enhancing the success of the new product. Specifically, pattern formation provides opportunities for people to shape, form, expand, and adjust their understandings about product-related concepts, objects, and events, thereby placing and seeing them in a larger NPD context and making sense of the ‘whole’ innovation process (Eoyang, 2007). Additionally, pattern formation reduces the tension inflicted upon product development efforts. For instance, when the task-related conflict evolves during the product development project, the pattern formation channels the mental and behavioral experiences of people to a narrow range of behavior, and reduces the number of projectrelated parameters, forming a logically coherent product development process (Cindea, 2006). Therefore, we hypothesize that: H3: Pattern formation is positively related to firm product innovativeness. Catalytic behavior of an organization also influences the product development activities by seeding positive feedback, creativity, and entrepreneurial activities. This is such that creating an environment where feedback, creativity, and entrepreneurship are expected and approved energize the innovative behavior. Indeed, as Latour (1992) noted, ideas need ‘energy’ to diffuse throughout the organization, and © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd that people, whether users or creators of the idea, must transform their idea into actions. Here, for instance, a lack of sufficient support (e.g., product or idea champion) during all the phases of innovative activities can cause new ideas and models to be abandoned (Hannah and Lester, 2009). Catalytic behavior of an organization also improves the collective learning efforts during the product development efforts. Specifically, people learn to supportively reason in a direction to formulate inferences that lead to the envisioned product-related solutions and outcomes (Latta and Kim, 2010), foster collective discussions and communication flow about how meaningful learning could take place due to limited time and resources (Hannah and Lester, 2009), and unlearn or eliminate previous information or knowledge to create new knowledge for better product development endeavors. Therefore: H4: Catalytic behavior is positively related to firm product innovativeness. 3.2. Mechanisms of CAS and adaptive management practices We posit that adaptive management practices influence the mechanisms of CAS. For instance, bonding behavior of management leverages the mechanism variables, for example, strategic resonance, by helping people act in a unified and interdependent manner (Barczak et al., 1987; Brett, 1996). Consequently, people (1) share their workloads with each other, and help each other in their tasks, (2) develop mutual personal friendship and empathy, as well as a high team spirit, and (3) tend to make better decisions than any single individual or department would make in a given situation (Haque, 2004). Indeed, bonding behavior of management does limit functional autonomy in formulating its working rules since people’s judgments are constrained by bounded rationality. Also, bonding behavior of management fosters social ties, and thereby speeds up the socialization process, enhancing catalytic behaviors and accreting nodes (Peppard, 2007). For example, people exploit information or knowledge through direct exchange with their colleagues by tapping each other’s networks. In this way, people also recognize each other’s values and routines, and appreciate each other’s abstract and tacit know-hows (Peppard, 2007). Further, bonding behavior of management enhances commitment among people to improve the effectiveness of pattern formation, such that people develop a mind-set that identifies them to their objects and courses of action (Torka et al., 2005). R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 23

- 7. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan As people have varied interests, abilities, and personal commitments, their identification, association, and commitment are also likely to vary. In this respect, bonding behavior of management provides the ability for people/departments/groups to carry out their strategic direction successfully and to maintain their means to implement. Therefore: H5: Bonding behavior of management is positively related to the development of mechanisms of CAS. Nonlinear behavior of management also influences the mechanisms of CAS (e.g., strategic resonance) by leveraging reciprocal, mutually causal, and interweaving influences among people and events (Mendenhall et al., 2000). For example, a reciprocal influence is the process through which each perception is concomitantly the outcome of the preceding action, and is the condition for the following action creating personal knowledge (Champagne et al., 2007). In this way, nonlinear behavior of the management creates a synergistic mind-set in the organization. Nonlinear behavior of management also offers a multiplier and recycling effect of information/knowledge generation, enhancing the mechanisms of CAS (Holland, 1995). For instance, a multiplier effect occurs when knowledge pass from people to other people, and possibly (likely) being transformed along the way, producing a chain of changes (Holland, 1995). Here, knowledge is recycled effectively, taking potentially new forms, with knowledge sharing supported with a diverse set of knowledge flows and a possibility for creating ad hoc knowledge flows. Finally, due to its historical perspective (e.g., connecting past, present, and projected future of the firm), nonlinear behavior of management helps people see the dynamic nature of work and business-related experiences of the firm, and offers an opportunity for them to frame experience in a way that opens up behavioral risk taking and expands the potential for creativity (Bussolari and Goodell, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesize that: H6: Nonlinear behavior of management is positively related to the development of mechanisms of CAS. We argue that attractor behavior of management leverages the mechanisms of CAS by providing people with visual images of the organization and environment (Boal and Schultz, 2007). For example, a compelling corporate vision represents an assertion that the adaptive efforts take their meaning from the whole firm and cannot be understood in isolation (Barczak et al., 1987). In this way, the management stabilizes divergent thoughts, feelings, and actions within and between them to enhance strategic resonance and knowledge expansion or accreting nodes 24 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 (Coleman et al., 2007). Attractor behavior of management also influences the mechanisms by acting as a tag (i.e., a flag or symbol around which everyone rallies and the philosophy that binds people together) (Marion and Uhl-Bien, 2001), such that management, as a tag, serves as a form of reference and a signal with which behavior can be compared, and mutual adjustment can occur, coordinates the activities of different people or departments, channels knowledge flows throughout the organization, promote and articulate an idea and an attitude, and provides organizations a long-term behavior or an identity for adaptiveness (Waldrop, 1992; Holland, 1995; Boal and Schultz, 2007; Pryor and Bright, 2007). Therefore: H7: Attractor behavior of management is positively related to the development of mechanisms of CAS. 3.3. Mechanisms of CAS, adaptive management practices, and product innovativeness We argue that as a driver of CAS mechanisms, adaptive management practices also influence the firm product innovativeness. For example, as a component of adaptive management practices, attractor behavior cultivates an innovative climate and orientation by enabling the encouragement of individual initiatives and clarifying the individual responsibilities (UhlBien et al., 2007; Carmeli et al., 2010). In this regard, people are able to solve product-related problems effectively, and enhance the capacity to respond technological and market-related changes. Nonlinear behavior also generates creative and adaptive knowledge that can impact product innovativeness. Here, people in the organization recognize the meaning of a given exchange, and adjust their own behavior as they respond to that meaning within the organization (Friedrich et al., 2009). That is, when people adjust themselves according to the new information, they expand their own behavioral repertoire, which in effect broadens the behavioral repertoire of the organization itself (Kauffman, 1993). Further, bonding behavior influences firm product innovation efforts by fostering interactions within and between social networks in such a way as to create and diffuse information across the organization. As people from different departments frame product-related issues according to their perspectives, the adaptive management practice of bonding behavior forms an organizing network to build their coalition and ally their complementary interests as well as resources (Hargrave and Van de Ven, 2006). We should also note that CAS mechanisms influence firm product innovativeness. In this respect, we © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 8. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness argue that these mechanisms mediate the adaptive management practices–product innovativeness link, which we empirically know little about so far. Specifically, the mechanisms allow adaptive management practices to function effectively for enhanced product innovation efforts, and actualize those practices and atmosphere into product innovation efforts. Therefore, we hypothesize that: H8: The mechanisms of CAS mediate the relationship between adaptive management practices and firm product innovativeness. 3.4. Environmental turbulence, adaptive management practices, and mechanisms of CAS We put forward that environmental turbulence has a triggering role on the adaptive management practices and CAS mechanisms in organizations. Specifically, the management literature indicates that environmental turbulence provides little reliable information, leading to ‘causal-ambiguity’ (Celly and Frazier, 1996). In this sense, when the external environment becomes more turbulent, and thus less predictable, organizations adjust their practices, processes, and routines to meet the challenges by aligning management practices and mechanisms (Beckman et al., 2004). For example, increasing changes in the market and technology-related information or knowledge (1) requires firms to acquire new information and then distribute it into organization quickly (Sawy and Majchrzak, 2004), (2) entails an effective information sharing using stories and feedback mechanisms, pattern forming, and sensemaking (Dougherty et al., 2000), and (3) increases the need of bonding and attractor behavior (Perrott, 2008). Also, quickly changing markets and technologies require quick responses and fast decisive actions for firms to take advantage of the external opportunities. Especially, catalytic behavior and strategic resonance of organization, for example, can facilitate a sense of agility, real-time, multidisciplinary analysis and prompt people to work more closely together in an attempt to buffer the unpredictability (Majchrzak et al., 2000). Therefore, we hypothesize that: H9: Environmental turbulence (i.e., market and technology turbulence) influences the adaptive management practices. H10: Environmental turbulence (i.e., market and technology turbulence) influences the mechanisms of CAS. © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd 4. Research method 4.1. Measures and sampling To test the above hypotheses, multi-item scales either adopted or developed from prior studies for the measurement of the variables were used. All variables were measured using 5-point Likert scales ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). Appendix A contains the questionnaire. A brief summary of the measures is presented in the following section. For strategic resonance in the organization, we developed new question items based on the past theoretical study of Brown and Fai (2006). We asked 14 question items indicating to what extent there are (1) continuous linkage and harmonization among people and departments, (2) people act in concert, and (3) there is cohesion and alignment between the firm’s capability and the market segment and technology. Regarding the pattern formation variable, we developed nine new question items, modified from the theoretical arguments of Osborn et al. (2002). The questions were designed to determine (1) to what extent people seek understanding of the situation via dialogue and discussion, (2) isolate and communicate which information is important, and (3) develop interpretive system to collectively pattern the situations. We used the theoretical study of Hannah and Lester (2009), Morse (2010), Uhl-Bien et al. (2007), and Marion and Uhl-Bien (2001) to operationalize the catalytic behavior variable. We modified and asked 11 question items to address the organizational view, including (1) to what extent people bridge communication gaps, (2) eliminate old knowledge, (3) facilitate continuous participation, and (4) construe social behavior in a multidimensional way for speeding up or enabling certain activities in the organization. For accreting nodes, we developed six new question items based on the arguments of Cacioppe and Edwards (2005) and Pavlovich (2009), including to what extent ideas and information/knowledge are magnified iteratively and disseminated throughout the organization. We asked seven question items to assess the nonlinear behavior of management derived from Uhl-Bien and Marion (2009) and Boal and Schultz (2007), including to what extent management stimulates dynamism, connects the past, present, and future of the firm, and creates organized disorder, etc. For bonding behavior of management, we asked nine question items derived from Uhl-Bien and Marion (2009), involving to what extent management fosters interconnectivity and diversity, provides a structure for information flow, and injects new ideas and R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 25

- 9. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan information into organization. We asked seven question items to assess the attractor behavior of management derived from Uhl-Bien and Marion (2009), Osborn et al. (2002), and Boal and Schultz (2007), including to what extent management acts as a tag (e.g., a flag around which everybody rallies), and recognizes attractors and understands the nature of the movement they create. The firm product innovativeness was assessed by asking five established question items adapted from Wang and Ahmed (2004), including to what extent a firm is first to market by new product and service introductions, firm’s new products and services are often perceived as novel by customers, and new products and services of firm put it up against its competitors. Environmental turbulence questions were adapted from Jaworski and Kohli (1993). Three question items each were asked for market and technology turbulence. Technology turbulence question items indicate the changes associated with new product technologies, and market turbulence question items show the changes in the composition of customers and their preferences. We should also note that although it is not the focus of our study, some variables were included as controls because they were shown to affect key variables in our study. For instance, researchers suggest that firm size and age can have significant influence on firm product innovativeness (e.g., Weiner and Mahoney, 1981). Firm size was indicated by the logarithm of the number of employees, and firm age was assessed by the logarithm of the number of years since the firm was founded. Also, as the product/ service development activities are perceived differently in different industries or sectors, we asked if the organization operates in the manufacturing/ production industry or in the service industry. After developing the new question items in English, three academics from US-based universities, who have industrial experiences of more than 10 years, evaluated the content and meaningfulness of the items to establish face validity. They did not note any difficulty in understanding the items or scales. These new and adopted question items were first translated into Turkish by one person and then retranslated into English by a second person using the paralleltranslation method. The two translators then jointly reconciled all the differences. A draft questionnaire was developed, and then evaluated and revised in discussions with three academics from Turkey, having knowledge on organizational behavior and innovation as expert judges. The suitability of the Turkish version of the questionnaires was then pretested by 10 parttime graduate students who are full-time employees 26 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 working in the industry. In addition, eight senior managers, randomly selected from a diverse cross-section of firms located in Istanbul, evaluated the content and meaningfulness of the items. Respondents did not demonstrate any difficulty understanding the items or scales. After confirming the questionnaire items, the questionnaires were distributed and collected by the authors, applying the ‘personally administrated questionnaire’ method. We used a stratified random sampling plan from the directory of Istanbul Chamber of Industry. The Istanbul district was chosen in order to decrease sampling error of the study because this district is the center of the Turkish economy for manufacturing and service sectors. A list of 350 eligible firms was generated from the directory of Istanbul Chamber of Industry. The firms were selected because they (1) develop new products and export them to other countries, such as United Kingdom, Germany, Arabic countries, Central Asia, and Russia; (2) are organized and managed based on a Western management style (e.g., they operate in accordance with ISO and European quality standards); (3) are affiliated with Western firms; and (4) have at least 30 employees, as suggested by Akgün et al. (2009). First, we contacted the firms’ general managers by telephone and explained them the aim of the study. Of the 350 firms contacted, 310 agreed to participate in the survey study. By using the procedure of Kumar et al. (1993), we asked for at least two respondents from each firm, who are the most knowledgeable about the organization’s operations, culture and employees, to fill out our surveys in order to reduce the single source bias. Those respondents are expected to serve as ‘key informants’ for others who work in the same organization (Kumar et al., 1993). In particular, we believe that those key informants are likely to assess the social interaction, relations among people, organizational knowledge, past experiences, and innovativeness more accurately due to their ‘bird’seye views’ of the organization. Also, we asked that the respondents have top-level positions in their respective areas and to be from different functions of the organization. Further, they should have been working in the firm for an average of over 5 years and have a college or graduate degree. Following the procedure of Podsakoff et al. (2003), we informed each participant that his/her responses would remain anonymous and would not be linked to them individually, nor to their companies or products. In addition, we assured respondents that there were no right or wrong answers, and that they should answer questions as honestly and forthrightly as possible. Of the 310 firms that agreed to participate, 259 completed our questionnaires. However, 24 firms © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 10. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness responded with only one survey, resulting in 235 firms. Since we asked for multiple responses from firms, we discarded these surveys from our analyses. Thus, our analyzable sample consisted of 235 firms with 497 surveys (some firms supplied more than two surveys). We compared the mean of variables, firm size, and ages of the eliminated surveys with the surveys used for the analysis, and found no statistical difference among them. In our sample, the respondents were senior employees/staffs (54%), senior engineers (22%), functional/department managers (11%), technical leaders (6%), product/project managers (3%), general managers (2%), and owners of the firm (2%). The respondent departments were finance (31%), engineering and design (28%), marketing (22%), manufacturing (12%), and human resources (7%). The participating industries included finance (22%), service (21%), machinery and manufacturing (15%), chemistry (9%), automotive (6%), metal (5%), information technologies (5%), pharmaceutical (3%), communication (3%), food (3%), electronics (3%), and textile (2%). 4.2. Common method variance assessment Since data for the independent and dependent variables are collected from the same informants, common method bias may lead to inflated estimates of the relationships between the variables (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). We checked for this potential problem using the Harman one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). The results of an unrotated principal component analysis indicate that common method variance does not pose a serious problem in our investigation because several factors with eigenvalue greater than 1 were identified – explaining 69.46% of the total variance – and because no factor accounts for almost all the variance (i.e., highest single variance extracted is 37.21%). In addition, following Lindell and Whitney (2001), we partialled out the smallest correlation of the remaining correlations in order to remove the effect of common method bias. Given that all unadjusted correlation coefficients remain statistically significant at P < 0.05 after adjusting for common method bias, we feel more confident that a serious threat of common method bias does not exist in this study. 5. Analysis and results 5.1. Measure validity and reliability We evaluated the reliability and validity of our variables using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). By using AMOS 4.0 (Arbuckle and Wothke, 1999), we investigated all 10 variables (involving 74 question items) in one CFA model using all surveys (n = 497). After the elimination of problematic items, which have cross loads, the resulting measurement model was found to fit the data reasonably well: χ2(989) = 2606.68, comparative fit index = 0.90, incremental fit index = 0.90, TuckerLewis index = 0.89, χ2/df = 2.67, and root mean square error of approximation = 0.05. Also, the parsimonious normed fit index = 0.77 is above the cutoff point of 0.70. In addition, all items loaded significantly on their respective constructs (with the lowest t-value being 2.50), providing support for convergent validity. To assess discriminant validity, a series of twofactor models, recommended by Bagozzi et al. (1991), were estimated in which individual factor correlations, one at a time, were restricted to unity by using AMOS 4.0. The fit of the restricted models was compared with that of the original model. In total, we performed 45 models – 90 pairs of comparisons – using AMOS 4.0. The chi-square change (Δχ2) in each model, constrained and unconstrained, were significant, Δχ2 > 3.84, which suggests that constructs demonstrate discriminant validity. Table 1 reports the reliabilities of the multiple items, along with construct correlations and descriptive statistics for the scales. Table 1 shows that there are some moderate to high correlations (ranges from r = 0.60 to r = 0.73) among some of the variables. However, we should note that we were expecting these scores because, in practice, for instance, developing information or knowledge through reciprocal interconnection is highly related to how people bridge the communication gap among others to speed up or enable certain activities (e.g., concept testing, prototype development, etc.). Table 1 also demonstrates that all the reliability estimates – including coefficient alphas, average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct, and AMOS 4.0 based composite reliabilities – are close to or beyond the threshold levels suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). As a check for discriminant validity, as suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981), the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than the latent factor correlations between pairs of constructs (see Table 1). After conducting these tests, we conclude that our measures have adequate discriminant and convergent validity. Finally, skewness ranges from −0.74 to 0.23, and kurtosis ranges from −0.72 to 0.78. These values are well below the level suggested for transformation of variables, skewness of 2, and kurtosis of 5, as indicated by Ghiselli et al. (1981). R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 27

- 11. 28 10 11 12 13 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 Composite reliability Variance extracted Cronbach’s α Inter-rater agreement (rwg) Diagonals show the square root of AVEs. *P < 0.1. **P < 0.05. ***P < 0.01. 9 10 11 12 13 8 7 0.88 0.64 0.88 0.74 0.90 0.56 0.90 0.73 0.88 0.65 0.89 0.86 0.86 0.54 0.86 0.75 0.89 0.56 0.89 0.76 0.86 0.55 0.85 0.76 0.79 0.51 0.79 0.75 0.90 0.68 0.91 0.74 0.77 0.53 0.77 0.72 0.87 0.70 0.86 0.76 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.77 0.89 0.87 0.43 NA 9 3.74 3.73 2.56 1.29 NA 8 0.88 7 3.07 6 0.79 5 3.28 4 Product innovativeness (0.80) Strategic resonance 0.55*** (0.75) Accreting nodes 0.50*** 0.70*** (0.81) Pattern formation 0.43*** 0.73*** 0.70*** (0.74) Catalytic behavior 0.41*** 0.71*** 0.73*** 0.70*** (0.75) Bonding behavior of 0.52*** 0.68*** 0.66*** 0.65*** 0.72*** (0.74) management Nonlinear behavior of 0.51*** 0.67*** 0.57*** 0.61*** 0.67*** 0.69*** (0.71) management Attractor behavior of 0.47*** 0.65*** 0.61*** 0.62*** 0.67*** 0.70*** 0.70*** (0.82) management Market turbulence 0.10** 0.17*** 0.29*** 0.21*** 0.29*** 0.21*** 0.22*** 0.19*** (0.73) Technology turbulence 0.11** 0.18*** 0.23*** 0.19*** 0.26*** 0.17*** 0.21*** 0.23*** 0.54*** (0.84) Firm size 0.11** 0.11** 0.10** 0.04 0.10** 0.08* 0.13** 0.08* −0.01 0.13*** – Firm age 0.07* 0.07 −0.01 −0.04 0.007 −0.08* 0.08* −0.01 −0.09 0.01 0.46*** – Industry −0.06 0.05 0.05 0.07 0.11** 0.08* 0.09* 0.06 0.14*** 0.26*** 0.16*** −0.08 – 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 0.89 0.74 0.85 0.74 0.79 0.83 2 3.59 3.52 3.37 3.28 3.26 3.32 1 Variables Mean Standard deviation Table 1. Correlations and descriptive statistics Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 12. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness 5.2. Hypothesis testing To test our hypotheses, we performed a structural equation modeling (SEM). However, before using the SEM analysis, as our unit of analysis is the ‘firm’, we first aggregated the question items of respondents, such that we got the average of each question item answered by the respondents in each firm. In our analysis, we found that all inter-rater agreement (rwg) values range from 0.72 to 0.86, well above the 0.60 benchmark (Hurley and Hult, 1998), indicating a satisfactory level of inter-rater agreement for each aggregate variable in a firm (see Table 1). After aggregating question items from individual (respondent) level to organizational level, we calculated the composite score for each of our variables and then used them in the SEM analysis. Also, consistent with CAS theory, we allowed the parameters representing the covariances across adaptive management practice-related variables and across CAS-related mechanism variables to be free during the analysis. Our analysis showed that most of the covariances are significant, indicating that there is a covariance among variables. This means that the variables occur simultaneously. These results also present an explanation for the moderate to high correlations among our variables. Table 2 indicates that strategic resonance (β = 0.39, P < 0.01) and accreting nodes (β = 0.29, P < 0.01) are positively related to the firm product innovativeness, supporting H1 and H2. However, we could not find any statistical relationship between pattern formation (β = 0.04, P > 0.1) and catalytic behavior (β = −0.13, P > 0.1), and firm product innovativeness; thus H3 and H4 are not statistically supported. Regarding the antecedents of mechanisms of CAS, Table 3 shows that bonding behavior of management is positively associated with strategic resonance (β = 0.30, P < 0.01), accreting nodes (β = 0.52, P < 0.01), pattern formation (β = 0.29, P < 0.01), and catalytic behavior (β = 0.42, P < 0.01), supporting H5. Also, our results demonstrated that nonlinear behavior of management is positively associated with strategic resonance (β = 0.29, P < 0.01), pattern formation (β = 0.16, P < 0.05), and catalytic behavior (β = 0.29, P < 0.01). However, we could not find any statistical association between nonlinear behavior of management and accreting nodes (β = 0.06, P > 0.1), partially supporting H6. Further, we found that attractor behavior of management is positively associated with strategic resonance (β = 0.23, P < 0.01), accreting nodes (β = 0.27, P < 0.01), pattern formation (β = 0.31, P < 0.01), and catalytic behavior (β = 0.22, P < 0.01), supporting H7. © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd Regarding the role of environmental turbulence on the adaptive management practices and mechanisms, we found that market turbulence is positively related to bonding behavior (β = 0.20, P < 0.01), nonlinear behavior (β = 0.20, P < 0.01), and attractor behavior (β = 0.13, P < 0.1). We also found that technology turbulence is positively related to nonlinear behavior (β = 0.13, P < 0.1) and attractor behavior (β = 0.21, P < 0.01), partially supporting H9. However, we could not find any statistical relationship between environmental turbulence variables and mechanism variables of CAS, thus not statistically supporting H10. In order to test the mediating effect of mechanisms between adaptive management practices and firm product innovativeness, we employed the Baron and Kenny (1986) procedure, where a variable (M) mediates the relationship between an independent variable (X) and a dependent variable (Y) if (a) X is significantly related to Y; (b) X is significantly related to M; (c) after X is controlled for, M remains significantly related to Y; and (d) after M is controlled for, the X – Y relationship is zero. Steps (b) and (c) are the essential steps in establishing mediation, and step (d) is only necessary to prove a fully mediated effect. Also, the presence of the mediator (M) must reduce the impact of the independent variable on the outcome compared with when M is not present. Further, entering the mediator into the AMOS-based SEM model should also result in a significant increase in R2. To address these issues, we performed three different SEM models, as shown in Table 3: • • • (a) model a, including all of the adaptive management variables (X) and the product innovativeness (Y), indicates that bonding behavior (β = 0.28, P < 0.01), nonlinear behavior (β = 0.15, P < 0.1), and attractor behavior (β = 0.16, P < 0.1) are positively related to the product innovativeness, and R2p.innov. = 0.32. (b) model b, covering the adaptive management variables (X) and mechanism variables (M), shows that all adaptive management variables are positively associated with all mechanism variables, except the relationship between nonlinear behavior and accreting nodes (β = −0.04, P > 0.1). (c) after adaptive management variables (X) are controlled, as shown in model c, it was found that strategic resonance (β = 0.27 P < 0.01) and accreting nodes (β = 0.27 P < 0.01) are positively associated with product innovativeness, whereas catalytic behavior (β = −0.31, P < 0.01) is negatively related to the product innovativeness. Also, mechanisms of CAS reduce the effects of R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 29

- 13. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan Table 2. Results of hypotheses Hypothesis Relationship Path value Stg. resonance → Product innovativeness Accreting nodes → Product innovativeness Pattern formation → Product innovativeness Catalytic behavior → Product innovativeness Bonding behavior → Stg. resonance H5 Bonding behavior → Accreting nodes Bonding behavior → Pattern formation Bonding behavior → Catalytic behavior Nonlinear behavior → Stg. resonance H6 Nonlinear behavior → Accreting nodes Nonlinear behavior → Pattern formation Nonlinear behavior → Catalytic behavior Attractor behavior → Stg. resonance H7 Attractor behavior → Accreting nodes Attractor behavior → Pattern formation Attractor behavior → Catalytic behavior Market turbulence → Bonding behavior Market turbulence → Nonlinear behavior H9a Market turbulence → Attractor behavior Technology turbulence → Bonding behavior Technology turbulence → Nonlinear behavior Technology turbulence → Attractor behavior Market turbulence → Stg. resonance Market turbulence → Accreting nodes Market turbulence → Pattern formation H9b Market turbulence → Catalytic behavior Technology turbulence → Stg. resonance Technology turbulence → Accreting nodes Technology turbulence → Pattern formation Technology turbulence → Catalytic behavior Control var. Firm size → Product innovativeness Firm age → Product innovativeness Industry → Product innovativeness χ2(34) = 91.86, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, χ2/df = 2.70, RMSEA = 0.08 H1 H2 H3 H4 Results 0.39*** 0.29*** 0.04 −0.13 0.30*** 0.52*** 0.29*** 0.42*** 0.29*** 0.06 0.16** 0.29*** 0.23*** 0.27*** 0.31*** 0.22*** 0.20*** 0.20*** 0.13* 0.12 0.13* 0.21*** −0.03 0.08 0.03 0.06 0.04 0.03 0.005 0.06 0.07 0.03 −0.09* Supported Supported Not supported Not supported Supported Partially Supported Supported Partially Supported Not supported Path coefficients are standardized. *P < 0.1. **P < 0.05. ***P < 0.01. CFI, comparative fit index’ IFI, incremental fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation. adaptive management variables on the product innovativeness, and inclusion of the strategic resonance, accreting nodes, pattern formation, and catalytic behavior in the model increased the R2 of product innovativeness (R2innov. = 0.38). management practices and product innovativeness, partially supporting H8. Based on the above results, it is seen that strategic resonance, accreting nodes, and catalytic behavior partially mediate the relationship between adaptive This study empirically showed that the mechanisms of CAS are related to firm product innovativeness, as shown in Figure 2. Specifically, we demonstrated 30 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 6. Discussion and implications © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 14. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness Table 3. Results of mediating hypothesis Relationship Model A Bonding behavior → Product innovativeness Nonlinear behavior → Product innovativeness Attractor behavior → Product innovativeness Bonding behavior → Stg. resonance Bonding behavior → Accreting nodes Bonding behavior → Pattern formation Bonding behavior → Catalytic behavior Nonlinear behavior → Stg. resonance Nonlinear behavior → Accreting nodes Nonlinear behavior → Pattern formation Nonlinear behavior → Catalytic behavior Attractor behavior → Stg. resonance Attractor behavior → Accreting nodes Attractor behavior → Pattern formation Attractor behavior → Catalytic behavior Stg. resonance → Product innovation Accreting nodes→ Product innovation Pattern formation → Product innovation Catalytic behavior. → Product innovation Firm size → Product innovativeness Firm age → Product innovativeness Industry → Product innovativeness Model B 0.28*** 0.15* 0.16* 0.29*** 0.54*** 0.30*** 0.43*** 0.29*** −0.04 0.16** 0.21*** 0.24*** 0.28*** 0.32*** 0.24*** 0.07 0.05 −0.11** χ2(11) = 39.22, CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.94, χ2/df = 3.56, RMSEA = 0.10 Full model Model C 0.16 0.15 0.08 0.29*** 0.54*** 0.30*** 0.43*** 0.29*** −0.04 0.16** 0.21*** 0.24*** 0.28*** 0.32*** 0.24*** 0.27*** 0.27*** 0.03 −0.31*** 0.05 0.03 −0.09* χ2(33) = 50.89, CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, χ2/df = 2.21, RMSEA = 0.07 Path coefficients are standardized. *P < 0.1. **P < 0.05. ***P < 0.01. CFI, comparative fit index; IFI, incremental fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation. Environmental conditions Adaptive management practices Mechanism of CAS Innovativeness Strategic resonance Bonding behavior Accreting nodes Market turb. Nonlinear behavior Firm product innovativeness Technology turb. Attractor behavior Pattern formation Catalytic behavior Figure 2. Actual model. CAS, complex adaptive system. © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 31

- 15. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan that strategic resonance of a firm positively impacts its product innovation efforts. This finding leverages the previous studies on the concept of ‘strategic resonance’. For instance, while previous studies showed the significant role of strategic resonance, for example, aligning technological and organizational capabilities with firm strategic implementation, on the success of process innovation efforts (Brown and Fai, 2006), we illustrated the critical role of strategic resonance on the success of product innovations, as suggested by Rodríguez-Pinto et al. (2008). This finding also improves our understanding on the alignment of organizational capabilities with strategic management in the NPD context. Specifically, while past studies showed the effects of alignment of technological, market, and NPD-marketing activities with a firm’s strategy on the market performance of new products (Acur et al., 2012), there are few studies investigating the effects of harmony between functional capabilities and strategic planning and formulation on the market success of new products. We showed that firm product innovativeness will be improved when firms’ R&D, marketing, and technological capabilities work in harmony and resonate with business-level strategy. Our results also empirically indicated that accreting nodes positively impact the firm’s chance to develop better and successful new products. This finding especially elevates our understanding on the fuzzy front-end stage of product development efforts, where user needs are discovered and product ideas generated, in the NPD literature (Reid and de Brentani, 2004). In particular, while previous studies argued that fuzzy front-end fits the CAS perspective, and proposed fewest strategies for effective management of it (see, Reid and de Brentani, 2004), we empirically showed that when ideas, information, and knowledge (1) are magnified iteratively or successively, as in a recurring growth pattern, (2) accumulation proceeds through selfconsistency and complementary beliefs, and (3) rapidly expand in importance throughout the organization, that firm develops better and successful new products, a product with a competitive advantage. Also, this finding expands the notion of the critical elements of effectiveness for information processing for successful product design and development efforts, such that we showed that people combine quality and speed of information, and enhance informal processes of networking and information sharing with the notion of accreting nodes, as argued by Brentani and Reid (2011). Interestingly, in this study, we could not find any statistical association between pattern formation and product innovativeness. One reason might be due to the significant covariances among mechanism 32 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 variables. That is, pattern formation affects product innovativeness via strategic resonance and accreting nodes. This finding empirically supports the theoretical arguments of Kraaijenbrink (2012), who discussed that pattern formation acts an agent role on the interactions among knowledge creation, application, integration, and retention, which have significant impact on product development project success. Another reason for the non-significant relation between pattern formation and firm innovativeness may be related to sensemaking process in the product development process. As noted by Weick et al. (2005), pattern formation (e.g., patterning of attention) is a part of the sensemaking process. For example, when people seek to understand the situations via dialogue and discussions, they end up with a fragmented organization of knowledge during the product development process. It appears that people need to integrate these patterns and to make them part of organizational knowledge base (e.g., organizational memory, project-related databases, etc.), engineering, or human factors for a successful product development process. In this study, we were also unable to find any statistical association between catalytic behavior and firm product innovativeness. The effects of the catalytic behavior on the product development efforts may be explained by the covariant role of strategic resonance and accreting nodes. Indeed, consistent with CAS literature, we showed that catalysts serve as executioners to enable actions, such as transforming strategic resonance and information/knowledge accreting into product development effectiveness (Lee and Sukoco, 2011; Mu and Di Benedetto, 2011). This study also demonstrated that adaptive management practices impact the mechanisms of CAS in the organizations. For example, when management fosters interconnectivity, creates linkages, develops moderately coupled structures in the organization, etc. (i.e., bonding behavior of management), people or departments (1) resonate and coordinate their actions, (2) expand their information/knowledge, (3) accelerate their actions, and (4) interpret and create patterns for new information. This finding leverages our understanding on the term of ‘dynamic networks of interaction’ in the innovation context, as highlighted by Uhl-Bien et al. (2007). In particular, unlike the static view of networks of interaction in the NPD literature (Allen et al., 2007; Ngai et al., 2008; Bstieler and Hemmert, 2010), we highlight the evolutionary nature of networks facilitated by management (Benson-Rea and Wilson, 2003). Also, we empirically illustrated that when management recognizes attractors and understands the nature of the movements they create, and acts as tags (i.e., © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- 16. System mechanisms, management practices, and firm product innovativeness attractor behavior of management), that organization will implement adaptive mechanisms more successfully. This finding increases our understanding of the concept of ‘organizational ambidexterity’ by highlighting the dynamic aspect of ambidexterity, as recommended by Raisch et al. (2009), and showing how organizations achieve ambidexterity, as noted by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004). Specifically, previous studies focused on the balanced view of ambidexterity (March, 1991; Cao et al., 2009), which is largely ‘static’ in nature, and indicates the optimal mix of exploitation and exploration at a point in time. With a CAS perspective in general and attractor behavior of management in particular, we showed that management can both sustain stability and respond to perturbation and initiate change in this study (Pryor and Bright, 2007). Attractor behavior of management also leverages our understanding on the role of management in the sensegiving process, which is the process of attempting to influence the sensemaking and meaning construction of people, in organizations (Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991). Sensegiving perspective has an assumption that sense can be owned by top management and that it can be given to people through active stages of influencing (Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991), or articulating that vision to others (Hill and Levenhagen, 1995) in the traditional writings. Here, we demonstrated that, especially with the tagging behavior of management, sense provided by management is produced with interactions with people, as people recognize management as a symbolic reference for their corresponding message (Holland, 1995; Boal and Schultz, 2007; Pryor and Bright, 2007). Further, we illustrated that nonlinear behavior of management where management connects the past, present, and projects the future of the firm through storytelling; stimulates dynamism, etc.; and improves the effectiveness of CAS-related mechanisms. This finding advances our understanding on the time aspect of improvisational behavior in the NPD literature (Moorman and Miner, 1998). While past studies reconcile linear and cyclical perspectives of time in organizations through the concept of improvisation (Crossan et al., 2005), they did not specify how to converge the time aspect of improvisation (Boal and Schultz, 2007). In this study, we showed that with organizational storytelling, managers blend past and expected future together in a deep experience of the present to become more adaptive to conditions. This finding also highlights the importance of counterfactual thinking (i.e., thoughts about what might have been), which was relatively understudied in the NPD context (Hsu et al., 2009). The literature indicates that counterfactual thoughts explore alternative realities © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd to past events, involves a reconstruction of the past, and have a powerful impact on how individuals approach the future. We showed that through storytelling and converging past, present, and projected future, management helps people see the dynamic nature of organizational experiences and offers a way to frame experience in a way that generate new possibilities, leading organization to become more adaptive. Next, our findings illustrated that the adaptive behavior of management is determined in a sense by the environmental context, such that management interacts and engages with the dynamic and complex market and technological conditions in which they operate to produce adaptive change for an organization. Interestingly, our results did not show any significant statistical relationship between environmental turbulence variables and mechanism variables. This finding shows that quickly changing technology and market information or knowledge stimulate the management for fostering adaptive efforts, and those efforts lead to strategic resonance, accreting nodes, catalytic behavior, and pattern forming. In a sense, adaptive management practices look like the ‘transmission mechanism’. This study, finally, enriched the view of firm adaptiveness in the literature by the use of CAS theory. It is seen that a CAS perspective provides flexible and responsive organizational structures (e.g., organic organizational structure), and fractal organizational design (e.g., a living organism). Also, by the use of CL theory, this study upgraded our understanding regarding the role of management in the turbulent conditions in the literature. Here, consistent with the theoretical argument (Uhl-Bien et al., 2007; Uhl-Bien and Marion, 2009), it appears that adaptive management occurs in the face of adaptive challenges (e.g., turbulent market and technological conditions), rather than technical problems, such as the application of proven solutions to known problems. From this research, the implications for managers are that the management should provide sufficient structure as well as enabling conditions to promote the adaptability and product innovativeness. Specifically, management should develop a master product innovation plan and then link the functional capabilities to that plan. Management should also blur some roles of R&D, manufacturing, and marketing functions so that they are diffused across the whole organization beyond functional-specific myopia. Also, the knowledge and understanding of what each function does need to be diffused throughout the organization. Indeed, functional specific myopia and core rigidities are issues that require insight and a concerted effort not to follow. Management further should provide R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 33

- 17. Ali E. Akgün, Halit Keskin, John C. Byrne and Özgün Ö. Ilhan enough resources (e.g., funding, information, and personnel) needed for product innovation efforts to the different departments and individuals (e.g., the usual guideline is to use an X percent of sales for funding such efforts), and foster a sense of unity and purpose (e.g., project vision) for them. Management should also develop transactive memory system in the organization by creating yellow pages, and a central database about the expertise of people for information and knowledge expansion. Management should also give some autonomy to people/functions, and form alliances and integration for information/knowledge expansion by creating advice and friendship networks. Next, management should allow experimentation and improvisation, and give freedom to people for the synthesis of new information/knowledge. Further, management could foster feedback culture, which indicates management’s support for feedback, including nonthreatening and behaviorally focused feedback, as well as coaching to help interpret and utilize feedback, throughout the organization. Management, next, should encourage storytelling, iterative dialogue, and collective problem solving; develop common languages; and use metaphors and symbols in order to generate new understandings about product innovation endeavors. Further, management should take the position of role model for the actions and adaptiveness. Indeed, when the environmental threat becomes overwhelming, people look at management to centralize authority and take action. This effect is particularly true when people feel they lack adequate resources or structure to address the threat. Finally, management should generate surprise (e.g., creating artificial crisis and anxiety) and select some people as knowledge catalysts (e.g., gatekeepers, informal leaders, who have social influence in the organization) in any learning initiative since management has limited time. 7. Limitations and future research There are some methodological limitations in this study. Specifically, due to the nature of the data, the generalizability of sampling is a limitation of this study. The study was conducted in a specific national context, Turkish firms in general and Istanbul district in particular. It is important to note that the readers should be cautious when generalizing the results to different cultural contexts. A Turkish sample involving the Istanbul district, like that of any culturally bound research, be it a major industrialized city in the United States, Europe, or Asia, etc., imposes some 34 R&D Management 44, 1, 2014 constraints on the interpretation and application of the results. Utilizing a cross-sectional design with questionnaires was also one of the limitations of this study. Even though ‘surveying is a large and growing area of research in the natural environment’ (Graziano and Raulin, 1997), the method used (only a questionnaire) may not provide objective results about the flow of information or knowledge, which is an inherently dynamic phenomena, throughout the organization. However, we should also mention that as a cross-sectional field study, this research provides some evidence of associations. We believe that the mechanisms of CAS and adaptive management practices of CL present opportunities for future researches in the NPD literature. For instance, the mechanisms of CAS can be expanded by including the variables of generation of both dynamically stable and unstable behavior, dissipation and phase transitions, and nonlinear change, etc. Also, the antecedents of the mechanisms can be studied in great detail. For instance, how the level of loosely coupled behavior and the number of people or departments engaged in the iterative dialogue in the organization influence the pattern formation of firms can be investigated. Next, how the organizational patterns emerge from the local agents and interactions, and the role of organizational boundaries and historical interactions on the pattern formation, can be studied in greater detail. Also, the concept of catalytic behavior can be expanded in the literature. For example, the roles of integration and collaboration among people; boundary experiences, which are ‘shared or joint activities that create a sense of community and an ability to transcend boundaries among participants’ (Feldman et al., 2006, p. 94); boundary objects ‘that engage participants in joint deliberation’ (Schneider, 2009, p. 61); and self-reinforcing behavior that people gain from successfully achieving a task and from a reliance on intrinsic rewards on the catalytic behavior can be investigated. Further, practices that lead to the effective expansion and accumulation of information or knowledge can be studied. For instance, fractal organizational designs, organizational improvisation, simultaneously autonomous and cooperative actions of people/departments, and dialectic and dialogic communication can be examined. In addition to the positive effects of adaptive management practices and mechanism of CAS on the product innovation, the reverse influence of them on the product innovation efforts should be considered in future researches. For instance, attractors can be understood as the boundedness of organization as they operate. In a sense, attractors are the limits within which product development projects operate. © 2013 RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd